This episode is the second in the “From Survival to Sanctuary,” series, where we’re collectively asking how we perform and build sanctuary, and how we move to enact and build collective care, in the service of liberation for all beings and bodies. This emergent offering of podcasts and texts is a sort of public research, where questions and hypotheses are the name of the game. But too it’s an invitation to humans I encounter and know to join me in brainstorming and sharing strategies for this work, which I believe needs to be done relationally, in feedback loops of vision and experience.

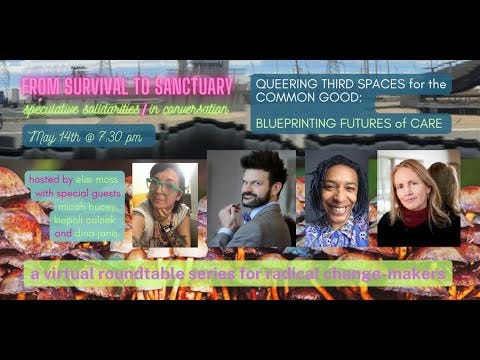

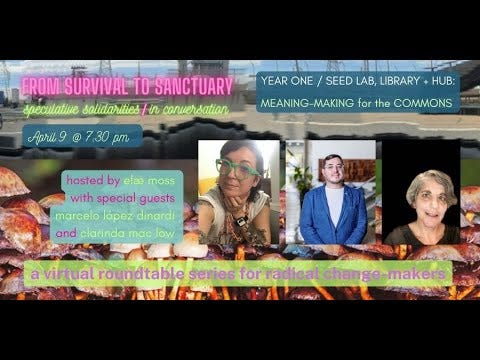

To carve out spaces for this dialogue, ‘From Survival to Sanctuary’ also exists as a free event series of the same name, where I’m joined in conversation by a truly stellar lineup of artists, thinkers, researchers, organizers, students, and radical faith leaders!

I hope you’ll join us for the upcoming two sessions, live on zoom this coming Tuesday on April 30th and then on May 14th! Each conversation is also available as a podcast and a YouTube video, with a full transcript and bonus content. Curious? Check out our April 9th episode, “Meaning-Making for the Commons,” here on substack!

Friends, let me tell you. As I’ve been writing and thinking and researching on “risk,” today’s intended topic, it became clear all the places it wanted to go could never fit in one episode.The question of risk is inescapable, as we consider what it looks like to to move from a conditioned state of SURVIVAL to one in which we’ve been able to shift our relationship to how we understand SAFETY, enough to believe that a sort of SANCTUARY can exist – and how we play an active role in co-creating it.

In our last episode, “The Get Along Gang,” we looked at the ways we make compromises to “get along.” Today, we’re diving into how and where we believe ourselves to be taking risks, and how this is linked to our perception of how and when and why we feel safe. We’re also asking what it means if some “risks” are not only responsible choices but necessary safety measures. What if choices framed as dangerous are the only way we reach a lasting, collectively built sanctuary state?

Before we really get into things today I want to stress how *personal* this work is, and what therefore it doesn’t seek to do or be. I’m explicitly seeking to recognize my experience as specific to me, as I look to explode my capacity for awareness outside my subjective mind and body.

I’ve spent a lot of time in and around academia, and around the sort of work and language that tries to make claims at “truth” and objectivity, and this is not at all trying to be that! though sometimes my language may lean towards sounding intellectual – which I think has more to do with my neurodivergence than anything else. When I encounter others’ words about their lives, and their observations and insights on the world I am both moved and grateful for the opportunity to become more aware of another’s inner life – simultaneously helping me see mine in a new light, and reminding me that each other-human-universe can at once be so similar to and so, so different from mine.

Truly my hope is that you might find some of the journeys I’ve gone on helpful for your own self-and-world discovery, that maybe it’ll spark something in you, your work, your relationships, or your community.

In the weeks I’ve been working on this, both personal and universal stories about threat and loss and fear have played out all around me. Yesterday, as I pulled the final strands together, I felt called to change the title to a line from “This Joy,” a lifegiving song originally released in 1985 by Pastor Shirley Caesar, covered recently by the amazing Resistance Revival Chorus.

I’ve put “This Joy” on many playlists these last years, and it’s lifted me up on countless days. But the song is serving as new medicine this week, watching students in New York and Atlanta singing its lines during their arrests at solidarity encampments. Yes, I’ll talk about “risk” today, but as much as possible I’m working to extract it from our survival conditioning as I do so. As we seek to build and become sanctuary my goal is to assist in this transmutation of self and perception, and I believe this requires a knowing that there is something inside us, call it power, call it joy, that we have – and THE WORLD DIDN’T GIVE IT and THE WORLD CAN’T TAKE IT AWAY.

When we’re considering not only how to act, but how to think and feel and be, now, this line offers a treasure to hold like a glowing ember. If you’ve clocked the subtitle you know that I still plan to dive into the meaty questions of [precarity and promised safety in the days of polycrisis], but what I’m looking for here is how to have a direct and re-oriented relationship to risk-taking, that reminds us that some risks are life-giving. This spellwork, this essential rewiring is called for in a moment where choices leading to increased precarity, threat, and risk along the metrics of the old paradigms are often the most necessary, beautiful, and hopeful acts of care we can make. I described this shift to a friend the other day using a metaphor about the game Jenga, which you’re likely familiar with, so I hope you’ll humor me using it again.

In this game, essentially, you’re stacking trios of wooden planks on top of each other until you build a tower and run out of blocks to create full levels with, at which point you begin removing individual planks from lower levels and placing them on top. To build higher requires an increasing destabilization of the base, and even with discerning removal and careful balancing, the tower eventually topples.My tarot people are waiting for a Tower card nod here, and I will not disappoint: within this system of human meaning-making (now over 500 years old, by the way), to pull the Tower represents a toppling of the status quo, taking both literal and symbolic forms.

But in this metaphor I am going in a bit of a different direction. I want to think about the ways that in the systems we inhabit we are not only the builder – the remover and placer of planks – but that we, too, are the planks. We are the materials from which the Tower is built. And in the transition from survival mode to sanctuary mode, we’re not actually putting those planks on the existing tower, we’re building a whole new structure. Maybe it’s not a tower at all, and we’re not even using that blueprint anymore. But the point is: we’re not putting them (or ourselves) on the old structure, even though we’ve been told that we can’t live without the tower, that the tower just… is.

What might it mean if we can take ourselves, our resources, and our understanding of what this all means out of the tower? When we’re asking ourselves about safety, and how to be safe, and how to build sanctuary, when we’ve left the tower, all bets are off. There isn’t really a lot of data about what is safe, because this iteration of what we’re building is just being born.

This metaphor only works up to a point, of course, but we can stretch it with a reminder that there are millions of Jenga sets, with other planks, offering infinite construction possibilities. And that these planks were at one point trees, and that we, these planks, the tower, are part of a much larger organism and a much larger story, within which the intelligence beyond that tower is and has always been the world into which we were born. The tower that pretends to be the world didn’t make you and cannot break you, if you understand yourself to exist beyond its rules.

Now friends – I do realize that dropping in a casual “exist beyond the rules of the system” recommendation is easier said than done, as is the concrete ask of putting oneself at physical risk in the interest of building new systems and ways of being.

This leap of faith is a huge one, but I do believe that there is substantial data that can assist us in rewiring the parts of our brains that have been fed scarcity models and fearmongering stories about what will happen if we take our jenga planks and selves out of the system – because those are stories told in fear, as there cannot be a system without us and our… planks. And every revolution to date, every movement relies on our coming to feel in our bodies that the people united can never be defeated – especially when we’re working with and honoring the earth, the larger planetary ecosystem, and all more-than-human entities, systems, and forces that not only accompany us here but that in fact we are made of.

I continue to be floored as I listen to Palestinians of faith speaking of those killed in the now 200 days of active genocide as martyrs. When I hear and receive their fervent belief that the souls of those lost to earthly life have not only not ended their journey but that their deaths are part of a larger battle against the misguided fears and violence of human occupation there is an unmistakable power to their conviction.

We may not agree exactly with what happens when people die, where consciousness goes or how it moves beyond this timeline or human body or earthly plane. For me, this precious possibility of being conscious within animated material is always a remarkable and in some ways unknowable thing. What I do know Is that I am part of systems of matter and power and intelligence far far beyond my control or capacity to perceive.

Which in turn reminds me that even if many refuse to acknowledge that we exist outside of the rules of the system, we physically exist outside the rules of the system anyway. The materials and forces out of which invented human systems have been wrought by their – by our – very makeup always exist outside of the invented rules of those invented systems.

These rules are mechanisms that seek to control the uncontrollable – to refuse to accept our unavoidable human awareness that this is… impossible. Ultimately, we are all at not only each other’s mercy, but facing the constant, imminent potentiality of forces beyond our comprehension.

A certain comfort with death – acknowledging death as not-end, as beginning, as life-cycle – changes our relationship to “risk,” as it does safety. When I think about spiritual safety I include death and human struggle as potentially being spiritually safe, or a “positive outcome,” in ways that can be challenging for us to parse. When I work with non-human entities or ancestors and I ask them for their guidance and support I recognize that my own limitations might preference outcomes or situations that in fact are not the ones I need most and so I try to remain humble in my awareness of how much I cannot know. Do with this what you will!

Meanwhile, I continue to toe the line of making choices that locate me, my body, and my “planks,” in the new paradigm, even while that landscape is unstable – imaginary, hypothetical, nascent, and iterating as it comes into being. Which is to say: I’ve chosen precarity, because sanctuary lives there.

I’ve chosen precarity. I’m continuing to choose precarity. I’ve been working out how this feels, and if I can find a way for these words to feel powerful. And I think the key is, like the fortune cookie game, to add “__in the old paradigm” to these phrases. I’ve chosen precarity… in the old paradigm, in the interest of building a new model. I’ve been building new systems and I see them blooming and see the students rising up and I believe in my heart and my soul and my spirit in people and interdependence and care. I live in this future. I do not live in the old paradigm and its metrics do not apply.

Well, that feels better. Because not only is this sort of “risk” not irresponsible, as we are gaslit to believe and fear in the old paradigm but it is deeply responsible… it is the only responsible choice, even for the people dead set on upholding the old ways. For their lives, too (and our planetary survival) depend on our risky responsibility.

TO CONSIDER:

Do you think of yourself as being at risk, or precarious? How do you understand that language to apply to you or other people? Do you believe that everyone is at risk?

I recently learned that the word “precarious” comes from the word-root for entreaty or prayer, that this language originates from a state of being “dependent on the will of another,” as our capacity for survival might be linked to the favor of a human… or forces beyond. I’m finding this important to think about as I consider who feels themselves to be at risk, even as it is challenging in terms of the ways in which we seek systemic change around deep inequity – because as we are observing, the feeling of being at risk (whether or not this can be substantiated) drives not only personal decisions but collective identity, politics and policy.

Judith Butler writes that “lives are by definition precarious: they can be expunged at will or by accident; their persistence is in no sense guaranteed. In some sense, this is a feature of all life, and there is no thinking of life which is not precarious.”

Leaning into the notion that all humans are subject to a sort of existential precarity presents a real challenge — especially for those of us who work to hold those in power or with greater resources accountable for the harm they cause. How can we balance a sort of collective human understanding of the ways that we may all act out of a desire to locate safety, with something akin to a fierce love, while also holding anger and insisting on corrective action, accountability, and repair?

I find myself returning to the way Lama Rod Owens grapples with anger as I think about this. Something I appreciate about Lama Rod is how he addresses our cultural frameworks of both anger and “violence” at the meeting place of activism, organizing, and spiritual practice, inviting us to acknowledge how we may be operating from a “reactive and compulsory” relationship to anger which is undermining our collective possibility for true and lasting change making.

I’m angry. So many people in my life are angry. And rightfully so. And: we want change.But who are we going to need to reach to get those changes to happen in a way that isn’t merely about power switching hands? This is a paradigm thing, again. From the position of the person in that tower, dedicated to the tower, who cannot see anything but a tower way of thinking and being – they can only imagine a new tower that works like the old tower. There is a fear that it will not be new, but the same, with those previously in power now in danger, oppressed, and abused – as they have done.

If you’re looking at my substack in text form, above this section you’ll find a montage featuring actor Jeremy Strong as Kendall Roy, in the HBO series Succession, a show which offers up a stark existential drama of the inner workings of the 1%. A fandom page about the show fed me a perfect quote for where I’m getting at, in including this show (and particularly this character) here: when talking about taking on the role of CEO in the media empire his father built, Kendall says, “I’m like a cog built to fit only one machine. If you don’t let me do this… I mean, it’s the only thing I know how to do.” How many people feel like this? Useless beyond what they know how to do in the only world they’ve ever known?

What we see in Kendall’s character in particular is a near psychosis, an alienation and array of defensive mechanisms that have developed as a result of existing in this rarified pressure-cooker. Variations on this theme are present in each character, in the family core and their financial, political, and social ties. Competition and “success” rule the day– there is nowhere safe here. Succession is a world without sanctuary, a world wherein care is only ever self-interested, and it is impossible to understand anything beyond the transactional. It is a chilling place, one that offers a window on the emotional drivers behind the curtain.

My takeaway is that at the top, there are scared humans who no longer believe that care or trust or even love is actually possible. Do I think that there can be certain… alliances perhaps....that prove their mettle over years of loyalty within this ecosystem, and that something akin to love can exist there? Perhaps, and I think we see glimmers of this in Succession, too – but then we see betrayals that cut so deep that they heighten the bitterness, further armoring each heart. And, if as Kendall says, this is all they know how to do, does it not make sense that they would fear abandonment by the rightfully angry in another future?

What does it look like to have conversations with someone operating from deep within this paradigm, even if they aren’t as deeply entrenched as the Roys? What does it mean to make our anger productive, to remain committed to accountability without deepening chasms of alienation and fear?If we’re going to have access to all of the materials for future building, we need to reckon with our collective precarity, to acknowledge our essential interdependence. To truly work with not only those who are sympathetic to the ideas or ways of thinking one believes in is a crucible.

How do I come to terms with and find a sort of empathy for the fears of people whose actions I find appalling? Who actively dislike and disrespect and wish harm upon me and the people I love? This may not mean I or we need to be in a room with these folks, but I do think it means acknowledging that others’ very human fears are behind every ideological battle. When approaching someone deep within the system, whose perceptions have been colored by the modes of competitive, fear-mongering survival, actual communication can feel impossible. But look at what I’m even doing here with this language – writing to a “you” that assumes a sympathetic audience, that most of my audience is already “like” me in some way, or at least sympathetic to listening to me.

Am I alienating potential listeners? Who do I appear to be, and am I building bridges or reinforcing differences? We make so many assumptions about the people we interact with, and some of the choices I make and ways I speak and talk and look reinforce these misconceptions about my identity and history. Because, to be frank, I was taught to do exactly that – like many people coming from poverty, in a working class immigrant family seeking to create a more stable footing in the United States, I learned to play the part.

But I also know I was taught to judge others and assess their position in relationship to my own in ways that replicate the same false narratives and assumptions that are being made about me. So I want always to return to the human, to remind myself not to narrativize others’ personal lives, history, and struggle until I’ve gotten a window onto their story – to remain curious, humble, and kind. Which is hard to do when we’re trained to see each other as a threat!

On this note, and before we scale back up to the systemic ways this is working, to more …thinky… observations about how risk might be operating for us, I want to get personal for a minute.

Like many of us, I have a bodymind striving to break free of the protective adaptations it created to keep me safe from repeating the harm of trauma. In my case, this took the form of decades of verbal abuse and growing up in an environment where my brain, bodily experience, and emotional life were invalidated, where gaslighting was constant and I came to doubt my own understanding of self and world and perception. This manifests in part as C-PTSD, inextricable from my experience of neurodivergence and chronic conditions exacerbated by the relationship between the nervous system, immune system, organs, and so on. The nature-nurture line here is an important one to walk, and as I continue to seek to name, understand, and navigate the always evolving ecosystem of my own organism I’ve sought to recognize the ways in which my body and brain are constantly working to keep me safe. From this standpoint, human survival instincts are in fact universal: something we’ve evolved to have, though the signals we send internally may be more appropriate for protection from a bear than the complex systems that put us at new and less straightforward kinds of risk.

An unexpected twist in my life recently found me at a wake in the Italian American enclave in Brooklyn I grew up in, with my accent creeping back in as I talked to relatives I haven’t seen in decades alongside the funeral director, Catholic deacon, hairdresser, a former Rikers CO, and neighbors across the spectrum of civil servant jobs most people in our families were encouraged to take as good and reliable jobs for the working class. It was quickly assessed that I was still good people, not a snob and not that kind of professor, and I felt at once relieved and at home, accepted and welcomed in with open arms – and totally an alien.

I took the risk of going. But I did not take the risk of attempting to correct everyone using my birthname or gender, responding with anything but shows of gratitude when described as a beautiful or smart or successful woman or girl or young lady. I also didn’t take the risk of correcting my mother’s performative pet naming of me, public kindness that masks the continued volatility and cruelty behind closed doors – a silent trigger that crept into my nervous system and had its way with me for the week that followed.

Trauma and abuse is a life-long teacher, and I’ve learned to have a certain type of sympathy for my mother’s own history and mental state, for the capacities not available to her. I know that I need to keep myself, for the most part, away from the faultlines of emotional and psychological risk that get activated when I’m in her company. In the stead of blood relatives, I’ve spent decades creating new types of family and community, studying and crafting modes of being with others and being myself. And I’ve committed to removing myself, and others, from people and places and systems that would abuse us – and building alternatives so that this escape is possible.

And yet: I’ve remained in and beholden to the tower, to a certain extent – the ivory one – through my somewhat accidental long relationship with academia. As institutions have turned over more and more to corporate models, conditions of adjunct labor have become more egregiously abusive, and the resultant conditions for students (and their freedom of speech and resistance) have hit peak fascism, as administrators call in police and military to repress peaceful protests. Increasingly precarious faculty like myself have been subject to threats and doxxing, and are constantly under scrutiny, fearful to lose whatever meager foothold they may have gained towards economic or professional security – risking their souls, their ethics, their dignity, in the name of “safety” within the tower. It’s a classic abuse scenario where the victim remains because of actual material reliance on the abuser – and one I’m familiar with from my own family.

My body screams this is unsafe, but the tower has trained me to understand this as my source of security – yet I’ve come to understand the risk of remaining as more profound than that of leaving, as I work through precarity beyond the old paradigm. I’ve chosen even within that system to operate as a fugitive for years (which in part is why it continues to feel so inhospitable), but increasingly I do not see it as risk but as responsibility to realize I’ve always been focused on world building beyond and despite the tower – to find my footing there, even as that ground shifts. I’ve often not understood those choices as choices, not seen those risks as responsible, but the rewiring is feeling more and more secure, less like cable I stole from the roof next door – and I’m suddenly able to feel proud of the ways I took the risks that made me insecure there despite my material precarity. That all along I’ve chosen freedom in the name of future sanctuary – that on some level, I’ve always believed it was possible, despite my body’s warnings otherwise.

TO CONSIDER:

Do you think of yourself as a person who takes risks, or think of yourself as someone who is risk-avoidant? What risks, if any, have you taken recently? Have you taken any today? This week? This month? This year? What risks have you avoided?

Did you easily identify risks for the question above? Let’s break these risks down into two categories, and see if your answers change.

1) When and how were you engaged in risks that you were choosing and naming as risk, making calculated or intentional decisions to do so?

2) When and how were you engaged in or exposed to threat or risk to which you were subject from forces outside yourself? What if anything does it change to acknowledge or name these as threat or risk? Do you experience yourself as having a choice in whether or not you are subject to these types of potential harm?

Recently I’ve found myself asking people if they feel like they’re living on borrowed time – it’s not meant to be a dark question, but it’s something I’ve begun to feel is an unspoken frequency that’s crept into the scene perhaps without being named or even noticed. And when I ask, the response is a fairly universal yes – and sometimes it turns into stories about how frequently this notion is popping up. Just this weekend, in fact, I asked a friend this question and they said, “Oh my god, I was just at the bike shop this morning and the guy there asked me the same thing!”I wonder, is it something you’ve been thinking about? What changes if we’re on borrowed time? And how does that feel for you – in your mind and in your body? For me, at least, this feels inextricably connected to the last question above: how it is that many of us feel forced to take on risks that we don’t feel we are choosing, or feel that we are only choosing between risks of different types, with safety never really an available option.

As I consider the choices I see others making, the shifts happening in myself and other people, I’ve been identifying what seems to me to be something willful, something almost… reckless…which varies widely in the quality it takes on, between hopeful defiance and a sort of low frequency of never totally absent anticipatory fear.

Sure, I’ll name it: the feeling or observation that “everything is falling apart,” is pretty much everywhere, and whether or not this is accurate or nuanced enough to be productive doesn’t change the way it feels, and the swings between overwhelm and fear and exhaustion and defiance and acceptance and avoidance I’m watching pretty much everyone I know cycle through. When I think about willfulness in this context, it takes radically different forms, some of which are probably not a perfectly appropriate use of the word. I guess I’m thinking about different ways I see myself and other people willing to act or making choices, which sometimes might take the form of taking risks, and often take the form of a sort of defiance. A lot of the moves I’d put in this category are choices made in relationship to our assessment of personal and collective danger: averting it, responding to it, or in a way, troubling it.

But the more I think about it the more I realize how complicated this is, because often the risks being taken simultaneously produce and threaten safety – along different systemic understandings, along different perceptual lines, and ultimately in different paradigms of living and being. I want to come back to what it means to think about these divergent paradigms of risk, because the notion about avoiding risk entirely as opposed to accepting risk, and learning how to address rupture and repair is essential to what I see as a new paradigm… which is also the oldest paradigm of all, because it’s how ecosystems work. (And, really, that’s what my early March Episode, a Field Log for Self-Immolation was about, if you want to go back and take a listen).

TO CONSIDER:

Before I name some examples, can you think of any actions, choices, or strategies (personal or collective) that could simultaneously be described as producing safety and creating risk, for the same people? (We can then extend this into how others perceive themselves to be impacted or threatened or kept safe by these’ actions and choices).

Did you come up with any? The more I think about this question, the more examples I find – and the more I’m aware of how critical it is to become literate in different narratives around risk and threat globally and historically.

We are the recipients of these lineages, and if we’re going to work towards sanctuary, it’s going to require us having not only an awareness but an embodied empathy to what this feels like for other bodies, even as we seek to inscribe counternarratives against intergenerational misinformation. I was born into a family where estrangement and fear loom large, born into stories of risk and threat and fault, which gives these considerations a particular and very personal place in my body’s ecosystem – a history which I now believe helps me understand somatically the way fears writ large so often find their roots in individual frightened bodies.

Right now, in the US we’re watching as peaceful student protests get framed as violent and couched in bigotry – as politicians and mainstream media sow division amongst those receiving only these skewed accounts of the proceedings through their screens and newsfeeds, far from what’s happening on the ground. And of course it’s not just student protests – from the last days I can relay accounts of arrests at and violent suppression of protests across campuses in the US as well as in Berlin and at the Gaza border, where Rabbis for Ceasefire had organized an action delivering aid meant to highlight starvation tactics.

This is nothing new, but what is easier to see and reframe our reaction to than ever before is how visible the machinations are: we can see how we are being manipulated, who is doing the manipulation, and what their goals are for our division. Recognition of this manipulation helps us realize our “instincts” are anything but natural, and it becomes our responsibility to decondition and relearn; while we may not be able to do this quickly, we can commit to an awareness of these machinations, and how they’re impacting all of us. When they show up, we need to have protocols for addressing our divergent reactions - lest they continue to rip our communities and relationships apart, and put us at even greater risk. I see the capacity to have these conversations around risk as absolutely necessary to move us towards repair.

Over the last years, as we’ve watched the global public fracture dramatically around responses to the pandemic and vaccine, protest movements, politics, and genocide, I don’t know a single person who hasn’t had their personal relationships deeply impacted if not irreparably changed. And at the heart of many of these rifts has been these diverging perspectives on and experiences of privilege and/or precarity. Even if we’re not actively addressing a creeping awareness of living on borrowed time, perhaps we can acknowledge that we are living in days where to be human is to feel threats at the door from which no one is totally safe.

The admission of the scale (and urgency) of not only potential but actual problems can feel so damning, so overwhelming, that to think about it at all can be damaging to one’s health, both mental and physical. And yet? Perhaps there is no time like the present to truly lean into possibility–to take the responsible risks of collective hope, to resist and rebuild, to rupture and repair. If we’re living on borrowed time, and willing to sit with the risks we’re taking on simply by being human at this time on our planet, it strikes me that maybe the wisdom of those at the end of their lives might be something to consider.

The top regret of the dying is reported to be that people wish they’d “had the courage to live a life true to [themselves], not the life others expected of [them].” What might your most responsible, most courageous, most true to yourself risk look like? I believe in my heart that our young people, that all of us out in the streets and in autonomous zones on campuses and beyond are laying out blueprints for us right now, and in so doing following in the footsteps of every principled revolution that has come before us.

Can you find your way in? Can you see how much you are being offered invitation, perhaps by turning on the translator? We’re not speaking in the language of the tower, we’re writing new dictionaries and you’re invited to contribute.

Let’s talk.

Share this post